Washington, D.C. Antique Car

and Historic Motor Vehicle Plates

Two separate and distinct antique vehicle-related registration types have been used in Washington, D.C.: Antique Car, issued from 1958 through early 1979, and Historic Motor Vehicle (HMV), issued since early 1979. The latter type replaced the former; that is, no Antique Car plates were issued or used after HMV plates were introduced.

| Antique Car |

Issued c.March 1958-Feb. 1979

|

|

|

The issuance of distinctive license plates for antique vehicles was approved by Congress with Public Law 85-273 on September 2, 1957. According to a January 1958 letter penned by the then assistant director of the D.C. Motor Vehicle Administration, the plates were expected to "go on sale approximately March 1, 1958." The actual introduction date is unknown. The annual registration fee was $5, where it remained until being raised to $9 in October 1976. The 1957 statute defines an antique car as a vehicle that "was manufactured prior to January 1, 1930, and is owned solely as a collector\\'s item, with its use limited to participation in club activities, exhibits, tours, parades, and similar uses, but in no event for general transportation."

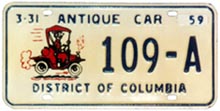

There are two distinct styles of Antique Car plate. The earlier is steel with a painted background, a letter A suffix to the number, and was validated with metal year tabs. Known samples, numbered 000-A, are believed to have not been available for general distribution, but rather were provided to auto hobbyists and others involved in the creation of the type at a meeting at which the design was unveiled and discussed. Based upon the timing of this type\'s introduction, the 1958 tab (marked "59") is believe to be the first. For how long tabs were used to validate these unusually heavy plates is unknown, but presumably stickers were introduced in March 1967, when they were for passenger car plates. What we\'ve been able to learn about Antique Car tabs, which were used only on plates of this type, is summarized here:

There are two distinct styles of Antique Car plate. The earlier is steel with a painted background, a letter A suffix to the number, and was validated with metal year tabs. Known samples, numbered 000-A, are believed to have not been available for general distribution, but rather were provided to auto hobbyists and others involved in the creation of the type at a meeting at which the design was unveiled and discussed. Based upon the timing of this type\'s introduction, the 1958 tab (marked "59") is believe to be the first. For how long tabs were used to validate these unusually heavy plates is unknown, but presumably stickers were introduced in March 1967, when they were for passenger car plates. What we\'ve been able to learn about Antique Car tabs, which were used only on plates of this type, is summarized here:

|

Registration |

Period |

Tab

Marked |

Tab Colors |

|

|

1958

|

April 1958-March 1959

|

59

|

blue on white

|

||

|

1959

|

April 1959-March 1960

|

60

|

|

||

|

1960

|

April 1960-March 1961

|

61

|

|

||

|

1961

|

April 1961-March 1962

|

62

|

|

||

|

1962

|

April 1962-March 1963

|

63

|

|

||

|

1963

|

April 1963-March 1964

|

64

|

black on white

|

||

|

1964

|

April 1964-March 1965

|

65

|

black on white

|

||

|

1965

|

April 1965-March 1966

|

66

|

|

||

|

1966

|

April 1966-March 1967

|

67

|

|

||

|

1967

|

white-on-green "68" stickers presumably were issued

|

||||

It is unknown when later Antique Car plates, which are aluminum with a reflective background, were introduced. They feature a letter A prefix to the number and were validated with stickers, and there are at least two varieties. Plate A-206, although reflective, has the expiration date ("3-31") embossed in the upper left corner and was made with a different die used to emboss the city name than was used on no. A-246 pictured below.

Antique Car was replaced by a new type, Historic Motor Vehicle, in February 1979 (as discussed below). At the time there were 21 sets of Antique Car plates in use, 13 of which were attached to Fords. It is believed that the series started at registration number 101-A. How high A-suffix numbers were issued before the letter was moved before the numbers is unknown, but we do know that the highest number issued was either A-223 or A-224. Plates numbered A-225 through A-250 had already been made when the type was discontinued in 1979, and some of these leftovers have found their way into the hands of collectors (as discussed in the final paragrah of the HMV section below). Thus, most Antique Car plates held by collectors today are of the reflective style and with numbers A-225 and higher. Stickers were never applied to these unused plates.

Antique Car was replaced by a new type, Historic Motor Vehicle, in February 1979 (as discussed below). At the time there were 21 sets of Antique Car plates in use, 13 of which were attached to Fords. It is believed that the series started at registration number 101-A. How high A-suffix numbers were issued before the letter was moved before the numbers is unknown, but we do know that the highest number issued was either A-223 or A-224. Plates numbered A-225 through A-250 had already been made when the type was discontinued in 1979, and some of these leftovers have found their way into the hands of collectors (as discussed in the final paragrah of the HMV section below). Thus, most Antique Car plates held by collectors today are of the reflective style and with numbers A-225 and higher. Stickers were never applied to these unused plates.

Although issued for slightly longer than 21 years, examples of this type are scarce today due to the small quantity made and issued.

|

|

| Historic Motor Vehicle |

First Issued: Feb. 1979

|

|

Type Designation: HMV

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HMV plates were issued at an amazingly slow rate until the past few years, when the pace appears to have increased. Registration number 217 was issued in Nov. 1984 whereas 629 was assigned in June 2003, almost 19 years later. Based upon these two plates it appears that an average of approximately 22 or 23 HMV registrations were issued annually during this period.

|

Historic Motor Vehicle plates have been issued continuously, albeit sporadically, since the type was introduced in February 1979 to replace Antique Car. Individuals to whom they are issued have always been required to renew their registration annually, which is to say these limited-use plates are not issued on a permanent basis for a one-time fee as are plates of the same and similar types issued in many of the states. The first expiration date for HMV plates was March  31, 1980, but (for reasons unknown) no expiration stickers were used from the type\'s inception until month and "84" year stickers were distributed in conjunction with the March 1983 renewal process (as staggered registrations were being introduced). Like D.C. plates of other types, the validity of HMV registrations is now indicated with a windshield sticker.

31, 1980, but (for reasons unknown) no expiration stickers were used from the type\'s inception until month and "84" year stickers were distributed in conjunction with the March 1983 renewal process (as staggered registrations were being introduced). Like D.C. plates of other types, the validity of HMV registrations is now indicated with a windshield sticker.

HMV plates may be used on vehicles that are at least 25 years old and vehicles at least 15 years old of a make that is no longer in production. Numbering began at HMV 1 in 1979 and proceeded sequentially. In December 1999, D.C. DMV Director Gwendolyn Mitchell testified (during a hearing on the District\'s year-of-manufacture plate law) that 475 historic motor vehicles were currently registered, although numbers being assigned at the time were undoubtedly higher. Number 629 is known to have been assigned in June 2003, and 1602 in June 2009.

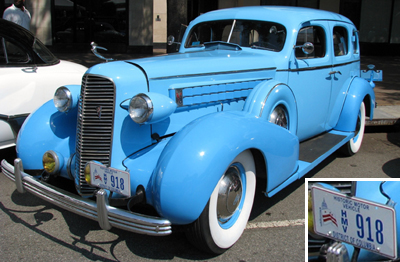

The format of HMV plates was changed upon the depletion of plates with an embossed registration number painted in red, which is thought to have occurred during 2006. Consistent with other D.C. plates made since mid-2001, current HMV markers are flat and feature a blue registration number. The change appears to have been made at plate number 900 or 901. Registration number 1000 was assigned in late 2006 or early 2007.

|

|

|

HMV plates on these cars suggest that the change from embossed plates with a red registration number to flat plates with a blue number occurred at registration number 900 or 901.

|

|

Creation of the Historic Motor Vehicle Registration Type

1973-1974: First HMV Bills Go Nowhere

By the early 1970s, when the Antique Car registration type had existed for about 15 years with no apparent modification, it became evident that at least an update to regulations governing the registration of antique autos in Washington, D.C. was needed. Evident, that is, to at least one Northwest resident. Shortly after purchasing two antique vehicles (a 1937 Lasalle and a 1954 Studebaker pickup) in 1973, Skip Lackie discovered that neither qualified as antique vehicles under the existing D.C. law, which stipulated that only vehicles manufactured prior to January 1, 1930 could be so registered. As he graciously prepared this HMV type history for DCplates.com, Mr. Lackie recalls that, given the restrictive nature of the Antique Car classification, relatively few of these registrations had ever been issued. He has no recollection of ever having seen an Antique Car plate in use, not even at old car shows.

Mr. Lackie\\'s incentive for working to change the way old cars were registered in the District was partly economic: because he was not permitted to purchase Antique Car plates for only $5 a year, he had to buy a class A passenger registration for his LaSalle at $50 annually and class B (truck) plates for the Studebaker at $69 a year. He writes that "the LaSalle was being driven less than 200 miles a year, which meant I was spending more per mile for license plates than I was for gas."

Mr. Lackie\\'s incentive for working to change the way old cars were registered in the District was partly economic: because he was not permitted to purchase Antique Car plates for only $5 a year, he had to buy a class A passenger registration for his LaSalle at $50 annually and class B (truck) plates for the Studebaker at $69 a year. He writes that "the LaSalle was being driven less than 200 miles a year, which meant I was spending more per mile for license plates than I was for gas."

Although a new structure of municipal government, with an elected mayor and city council, was to be implemented at the beginning of 1975, Mr. Lackie decided to try to update the law during 1974 while Congress was still in charge. (He writes today, however, that "with the wisdom that comes from having observed Congress in action for more than 40 years, I now see how stupid that was.") In early 1974 he contacted his non-voting Congressional delegate, Walter Fauntroy, about modifying the D.C. antique vehicle law. Mr. Fauntroy responded that he had introduced similar legislation in Congress in 1973 but that essentially no action had been taken on it. The bill had proposed simply changing the 1930 limit for qualifying vehicles to allow vehicles "at least 25 years old" to be registered with Antique Car plates. "Had his bill actually passed in Congress," writes Mr. Lackie, "I probably would have been satisfied with the situation and not pursued the matter further."

With the lack of action on the 1973 bill, Mr. Lackie recognized an opportunity to improve the next similar bill by including language that would provide needed protection for old cars. "At the time," he writes, "there was a lot of pressure from safety and environmental groups to require that all cars be retrofitted with modern innovations such as seat belts and emissions-reduction equipment. Antique vehicle owners know that the installation of modern equipment on their cars may be both difficult and expensive, and usually also means a lower score when being judged for authenticity. In general, federal laws that require the use of safety or emissions equipment allow the states to exempt antique and historic vehicles from such requirements, but each state has to take formal action to do so." With copies of recently-enacted antique auto laws from several states used for reference, Mr. Lackie drafted a new historic motor vehicle act for D.C. The draft bill was submitted to Rep. Fauntroy, who passed it along to the Subcommittee on D.C. Business, Commerce and Taxation, where it died.

In January 1975, as the new City Council assumed most responsibilities formerly vested in Congress, it became clear to Mr. Lackie that it was going to take more than just his own efforts to get the group of newly-elected council members to consider a new law. Having been accumulating names and addresses of members of old car clubs that were D.C. residents, by this time he had assembled a list of about 95 people that belonged to 13 different organizations. He sent to each person a copy of his proposed new law with a request for their support, and the 20 or so that responded were invited to an April 20, 1975, meeting on the subject. "Thus was born our own lobbying group," writes Mr. Lackie, the D.C. Auto Club Council. One of the meeting attendees was Sean Rogers, an attorney who owned a Hudson, and he and Mr. Lackie became the co-chairs (and sole active members) of the DCACC. The proposed law was slightly modified and in June a copy was mailed to individuals included on the original list of almost 100 old car enthusiasts for their vote: yes, no, or maybe with modifications. Fifty-two of the 55 respondents voted "yes" and three voted "maybe." Nobody was against the measure.

One of the respondents was the D.C. resident who had contacted Rep. Fauntroy in 1973 about updating the original Antique Car law. Alvin Harper wanted the law changed so that he didn\\'t have to subject his 1930 Ford Model A to the required annual safety inspection. (D.C. has had a motor vehicle inspection program since 1938, and has always used government-owned inspections stations staffed with civil servants, as opposed to commercial service stations, to conduct its inspections. Many of the inspectors are unfamiliar with antique cars, increasing the risk of problems during the process.) Because Mr. Harper\'s Ford had been built in early 1930, under the existing law it missed qualifying for Antique Car plates by a few weeks. Furthermore, workers at the inspection station had damaged the suspension of his car when its front end was being checked for looseness. Not only did he support the proposed new law, but he knew one of the newly-elected city council members, David Clarke. A meeting was held with Mr. Clarke in May 1975, and although encouraging, like any good politician he wanted to know how many constituents might be affected by the issue. He asked about how widespread the old car hobby was in the District. Mr. Lackie recalls that "although the list of 95 residents looked more impressive than it really was, because we had never heard from about half of those on the list, it seemed to satisfy him."

One of the respondents was the D.C. resident who had contacted Rep. Fauntroy in 1973 about updating the original Antique Car law. Alvin Harper wanted the law changed so that he didn\\'t have to subject his 1930 Ford Model A to the required annual safety inspection. (D.C. has had a motor vehicle inspection program since 1938, and has always used government-owned inspections stations staffed with civil servants, as opposed to commercial service stations, to conduct its inspections. Many of the inspectors are unfamiliar with antique cars, increasing the risk of problems during the process.) Because Mr. Harper\'s Ford had been built in early 1930, under the existing law it missed qualifying for Antique Car plates by a few weeks. Furthermore, workers at the inspection station had damaged the suspension of his car when its front end was being checked for looseness. Not only did he support the proposed new law, but he knew one of the newly-elected city council members, David Clarke. A meeting was held with Mr. Clarke in May 1975, and although encouraging, like any good politician he wanted to know how many constituents might be affected by the issue. He asked about how widespread the old car hobby was in the District. Mr. Lackie recalls that "although the list of 95 residents looked more impressive than it really was, because we had never heard from about half of those on the list, it seemed to satisfy him."

Those involved in the effort soon learned that their proposed bill would have to be broken up into several pieces because amendments were actually being proposed to several different sections of existing D.C. law. Furthermore, the terminology had to be modified to conform to the legal language already in use in related chapters. This task fell largely to Mr. Rogers, who worked on the project with Mr. Clarke\\'s legal staff. Finally, in July 1976 Mr. Clarke introduced the "Historic Vehicle Act of 1976" into the city council. Although one or two minor provisions had been deleted, Mr. Lackie recalls being "pleasantly surprised at how faithfully Clarke and his staff had preserved our ideas." The bill was referred to the Committee on Transportation and Environmental Affairs for consideration, where it died.

Early 1977: Laying the Groundwork for a Successful HMV Bill

During the 1975-76 effort Mr. Rogers and Mr. Lackie had solicited support from all 95 DCACC "members," and at least some of them furthered the cause by writing to their council members. Mr. Clarke reintroduced the bill on February 9, 1977, as the Historic Vehicle Act of 1977, and this time it was referred to the Committee on Finance and Revenue, a change that apparently angered members of the now bypassed Transportation and Environmental Affairs Committee. Council member (and later mayor) Marion Barry chaired the Finance and Revenue Committee, and while it was obvious that he didn\\'t care about old cars he also saw no reason not to take action on the bill. It was farmed out for comment to the Executive (the mayor\\'s office, corporation counsel, and DMV and its parent agency, the D.C. Department of Transportation) as well as to the Transportation and Environmental Affairs Committee, which had taken no action on it the year before.

Messrs. Lackie and Rogers met with Councilman Barry\'s staff several times to negotiate changes as deemed necessary. The negotiations became intense, even heated at times as they tried to defend various provisions of the bill, which provided for the display of HMV plates on any vehicle at least 25 years old, on orphans (makes no longer manufactured) when only 15 years old, and on vehicles determined to be unique, experimental, or built in token quantities also when 15  years old. This latter provision drew the most fire even though there probably were no such vehicles registered in the District. The city council was unwilling to delegate to the DMV the authority to determine which vehicles could qualify under this provision, and no other candidate agencies made sense. Rogers and Lackie eventually gave up fighting for that phrase but were able to keep the provision for 15-year-old orphans intact. At the time there were quite a few makes and distinct car lines that had ceased production within the past 25 years, including Studebaker, Packard, Hudson, Nash, Edsel, DeSoto, Corvair, and a number of British makes. Corvairs presented a unique problem because they had always been registered simply as Chevrolets in the District. Although Mr. Lackie astutely pointed out that Corvair vehicle identification numbers (VIN) included a character by which Chevrolet\'s 1960-69 air-cooled, rear-engine machines could be identified, this battle was lost. Ironically, however, Mr. Lackie writes that "about five years after the bill became law, the new director of the DMV called me to ask if Corvairs were eligible for historic plates when only 15 years old. I told him that a strict reading of the law would say no, but that I thought that they should have been included. He said that he thought so too, and would approve their use on a 15-year old Corvair. So much for the letter of the law!" The version of the law that was ultimately enacted actually included a list of orphan makes specifically authorized at 15 years old: "Kaiser, Hudson, DeSoto, Nash, Edsel, Studebacker (sic), and Packard".

years old. This latter provision drew the most fire even though there probably were no such vehicles registered in the District. The city council was unwilling to delegate to the DMV the authority to determine which vehicles could qualify under this provision, and no other candidate agencies made sense. Rogers and Lackie eventually gave up fighting for that phrase but were able to keep the provision for 15-year-old orphans intact. At the time there were quite a few makes and distinct car lines that had ceased production within the past 25 years, including Studebaker, Packard, Hudson, Nash, Edsel, DeSoto, Corvair, and a number of British makes. Corvairs presented a unique problem because they had always been registered simply as Chevrolets in the District. Although Mr. Lackie astutely pointed out that Corvair vehicle identification numbers (VIN) included a character by which Chevrolet\'s 1960-69 air-cooled, rear-engine machines could be identified, this battle was lost. Ironically, however, Mr. Lackie writes that "about five years after the bill became law, the new director of the DMV called me to ask if Corvairs were eligible for historic plates when only 15 years old. I told him that a strict reading of the law would say no, but that I thought that they should have been included. He said that he thought so too, and would approve their use on a 15-year old Corvair. So much for the letter of the law!" The version of the law that was ultimately enacted actually included a list of orphan makes specifically authorized at 15 years old: "Kaiser, Hudson, DeSoto, Nash, Edsel, Studebacker (sic), and Packard".

The Corvair VIN issue, recalls Mr. Lackie, is a good example of the many challenges faced by he and his team. "We knew more about cars, and even registration systems, than did many people working for the DMV, and certainly more than members of the city council. On numerous occasions we had to (politely) point out that their assertions were incorrect or that solutions to perceived problems were readily available and straightforward to implement. Groups in several states were then lobbying for the same kinds of protections for old cars as we were in D.C., and they had provided me with a lot of material on how their states had solved similar problems. Nevertheless, the DMV had a lot of power, and they had to be treated with respect. On the other hand, many of their suggestions were helpful. For example, our bill exempted historic vehicles from annual safety inspections but we had failed to also exempt them from the inspection fee and from displaying an inspection sticker." The DMV ultimately insisted on a one-time initial inspection to ensure that the historic vehicle was not equipped with a modern drive train (based on a similar Delaware law), but agreed to not require subsequent annual inspections and the corresponding stickers.

The biggest challenge faced at this stage was responding to the assertion that there were thousands of 25-year-old cars running around the District and that allowing them all to be registered with HMV plates would result in both an enormous revenue loss for the city government and anincrease the number of uninspected clunkers being operated in the city. Lackie and Rogers were able to provide officials with a Special Interest Autos article that showed that (at that time) after 15 years only 5% of a particular model year\'s output was still in use. Furthermore, the SIA analysis showed that after 18 years only 1% were still registered. Promoters of the HMV bill were helped by the DMV never being able to get its computers to answer the model year attrition question for D.C.-registered vehicles. The DMV insisted that the bill include language to require working lights, a horn, and unmarred glass, and that prohibited excessive smoke and noise. Their additions also prohibited the installation of a television set within view of the driver, "which was certainly not something that we had considered," notes Mr. Lackie.

Mid-1977: Steady Progress Leads to Success

Three DCACC members attended a June 15,1977, meeting of the Committee on Revenue and Finance convened to discuss the HMV bill. In the group\'s letter of introduction, Mr. Rogers claimed that the delegates represented about 500 owners of antique cars in the District - a very optimistic estimate! They made a few remarks and then waited for questions. Although none were forthcoming from members of Councilman Barry\'s committee, quite a few were posed by the Transportation and Environmental Committee staff as well as Robert Landolt, representing the D.C. DOT. Mr. Landolt had obviously researched the issue, and once DCACC representatives had satisfied him, all other opposition melted away. Of the expeditious end to the meeting, Mr. Lackie recalls that "A televised press conference on another matter had been scheduled a bit later that afternoon, and all the city council members wanted to wrap up our meeting as quickly as possible so they could be in camera range for that. The committee approved the bill four votes to none, with one abstention. I\'ve always had the feeling that council members Clarke and Barry were the only ones on the committee that had even bothered to read the text of the bill."

Historic Vehicle Act of 1977 went before the full city council for its first reading on the evening of July 26, 1977. Fortunately for interested visitors to the meeting it was heard tenth of 44 agenda items. The committee staff introduced the bill, and Mr. Lackie and his team answered a few questions from the Council. "I remember that one council member claimed that her constituents were so poor that most of them owned cars more than 25 years old, and she was sure they\'d all run out and buy the $9 historic tags to save money and avoid inspection," he recalls. "I responded that the DMV had been unable to come up with a firm figure, but that they estimated there were only two or three hundred cars over 25 years old registered in the District, and that very few of them were being used as daily drivers." Another question arose about 15-year-old orphan makes being allowed to be registered with historic plates, an issue about which the DMV had actually been able to provide some data. Registered in the District at the time were 42 cars that qualified as orphans under the bill, but two of them (both Packards) were built before 1930 and already qualified as antiques under the existing statute. Hearing that, the council lost interest in the matter and approved the bill unanimously. It passed its second reading in September 1977, and was signed by Mayor Walter Washington shortly thereafter.

Historic Vehicle Act of 1977 went before the full city council for its first reading on the evening of July 26, 1977. Fortunately for interested visitors to the meeting it was heard tenth of 44 agenda items. The committee staff introduced the bill, and Mr. Lackie and his team answered a few questions from the Council. "I remember that one council member claimed that her constituents were so poor that most of them owned cars more than 25 years old, and she was sure they\'d all run out and buy the $9 historic tags to save money and avoid inspection," he recalls. "I responded that the DMV had been unable to come up with a firm figure, but that they estimated there were only two or three hundred cars over 25 years old registered in the District, and that very few of them were being used as daily drivers." Another question arose about 15-year-old orphan makes being allowed to be registered with historic plates, an issue about which the DMV had actually been able to provide some data. Registered in the District at the time were 42 cars that qualified as orphans under the bill, but two of them (both Packards) were built before 1930 and already qualified as antiques under the existing statute. Hearing that, the council lost interest in the matter and approved the bill unanimously. It passed its second reading in September 1977, and was signed by Mayor Walter Washington shortly thereafter.

Because laws in Washington, D.C are ultimately controlled by Congress, the Historic Vehicle Act of 1977 would not become law until after the passage of 30 legislative days, during which that body had the right to veto it. A legislative day is one in which Congress is in session. Rogers and Lackie and their team assumed that Congress would work five days a week, so 30 legislative days would equal about six weeks, perpetuating hopes that the new system would take effect in time for the annual registration renewal period in March 1978. This, of course, was not to be. Congress only works about 100 days a year, so 30 legislative days did not pass until well into the spring of 1978. Nevertheless, a final letter was dispatched to DCACC members informing them that their efforts had been successful.

Designing the HMV Plates

Messrs. Lackie and Rogers contacted the D.C. DMV early in 1978 in an attempt to influence the design of the new Historic Motor Vehicle plates. They were, of course, assuming that new plates would be issued because the word "antique," displayed prominently on Antique Car plates, was not included in the new law. "Unfortunately, the DMV was not interested in discussing the matter with us," writes Mr. Lackie almost 30 years later. "We had difficulty in making appointments with them, and even when we succeeded they either sent an uninformed underling or failed to show up at all. After several months of trying to approach them we finally figured out that the DMV had no intention of ever negotiating with us over anything. I don\'t think they were mad at us for having come up with the new law. Rather I think it was the normal hubris that comes from being in charge of something - the "we know what we\'re doing, we don\'t need any help from amateurs\' attitude."

As the spring of 1978 turned into summer Rogers and Lackie knew they were losing their chance to influence the design of the new plates. The DMV was sure to need a substantial period of time during which to order and await the reflective sheeting from 3M and then have the plates made at Lorton Reformatory in time for issuance during the March 1979 renewal period. Fortunately, Mr. Rogers, an attorney, "knew some people who knew some people." He was able to contact Douglas Schneider, director of the D.C. DOT, and explain the situation. Although he likely thought the whole issue was rather trivial he called the DMV director and told him to cooperate with the committee, and he directed his assistant, Robert Landolt, to monitor progress. As it turned out, Mr. Landolt actually attended most of the meetings that followed and overruled the DMV on a few occasions.

Because the new law was relatively explicit on most matters, the major topic of debate was the design of the plates themselves. The first debate was over how the city name would be displayed. "Washington, D.C." had been used on most plates issued since March 1965, but Mr. Lackie felt that "District of Columbia" would be more appropriate for use on old cars. "DMV officials really didn\'t care that much one way or the other, so they agreed to District of Columbia."

Next to be addressed was the graphic design. The existing Antique Car plate included a cartoon of a Model T-like old car, puffing steam and smoke, complete with mustachioed driver. Nobody on the DCACC-based committee liked it, and all felt that the depiction of any old car was inappropriate because it wouldn\'t be many years before the plates were mounted on relatively modern 1950s and 1960s vehicles. A decision was therefore made to use a patriotic design. Given that the District is the nation\'s capital, including the Capitol dome seemed appropriate, although all of the D.C. residents working on the project realized that their city is far more than the seat of government: ordinary citizens live here, too. "I pushed hard for [inclusion of the D.C. flag] as a demonstration of this \'other\' D.C.," writes Mr. Lackie. "Our little committee liked it, and my wife (a commercial artist) prepared an illustration of the flag flying in front of the Capitol dome." Both the DMV and the D.C. DOT approved it after some grousing about how much 3M was likely to charge for making the sheeting. Committee members appropriately pointed out that the plates were likely to be in use for decades without change, so an attractive design was a worthwhile investment. In the end, 3M was able to use Mrs. Lackie\'s drawing without alteration, saving a little money. The flag had to be red, so the Capitol dome was printed in blue.

Next to be addressed was the graphic design. The existing Antique Car plate included a cartoon of a Model T-like old car, puffing steam and smoke, complete with mustachioed driver. Nobody on the DCACC-based committee liked it, and all felt that the depiction of any old car was inappropriate because it wouldn\'t be many years before the plates were mounted on relatively modern 1950s and 1960s vehicles. A decision was therefore made to use a patriotic design. Given that the District is the nation\'s capital, including the Capitol dome seemed appropriate, although all of the D.C. residents working on the project realized that their city is far more than the seat of government: ordinary citizens live here, too. "I pushed hard for [inclusion of the D.C. flag] as a demonstration of this \'other\' D.C.," writes Mr. Lackie. "Our little committee liked it, and my wife (a commercial artist) prepared an illustration of the flag flying in front of the Capitol dome." Both the DMV and the D.C. DOT approved it after some grousing about how much 3M was likely to charge for making the sheeting. Committee members appropriately pointed out that the plates were likely to be in use for decades without change, so an attractive design was a worthwhile investment. In the end, 3M was able to use Mrs. Lackie\'s drawing without alteration, saving a little money. The flag had to be red, so the Capitol dome was printed in blue.

HMV Plate Numbering

The registration number format and starting point turned out to be, by far, the most contentious issue encountered during the entire process. DCACC members involved thought that the DMV would continue the A-prefix (or suffix) series simply because the law did not specify anything about the numbering configuration. The DMV vetoed that, however, because the law specifically used the term "historic". Use of an H prefix was not possible because it was already in use on Hire (taxi) plates, and although HV seemed like a good idea to some, the DMV wanted to save it for possible future use on plates assigned to handicapped motorists. In the end, the rather ponderous HMV was settled upon. Because there wasn\\'t room for both the chosen graphic and six registration characters, the DMV grudgingly agreed to stack the HMV prefix in the center of the plate and put the numbers to its right. Officials expressed some concern over the possibility of running out of numbers because there would not be enough room to go beyond HMV999. We assured them that none of us would live long enough to see that happen, although in fact plate numbers are now above HMV 1000, with the vertical three-letter prefix moved slightly to the left to accommodate the fourth digit. As of mid-2007 numbers were being issued in the vicinity of HMV 1010 to HMV 1020.

With the type designation (prefix) letters determined, attention turned to the numbers that would follow. Since the adoption of uniform 6" x 12" plates throughout the U.S. in the mid-1950s, the District had generally included a minimum of three numerals on non-passenger plates. Serial numbers below 100, with leading zeros (e.g. CA-012), were initially used, however with the adoption of black-on-white non-passenger plates in March 1965 the starting point for non-passenger series was changed to 101 (e.g. commercial plates began at C-101.) (A notable exception was made for diplomatic plates, of which the most senior ambassadors were assigned the lowest numbers beginning with DPL-1.) Members of the DCACC committee wanted the new plates to begin with number HMV 1, but the DMV refused, stating that its policy was to include at least three number on all non-passenger plates. "They did back down to a little, agreeing to start the series at HMV 001, but we held out for starting it at HMV 1" writes Mr. Lackie. "In one meeting the DMV stated that they did not want to preclude someone with the initials H.M.V. from getting personalized plates with numbers HMV 1, HMV 2, etc., and that, in fact, those numbers might already be in use on personalized plates, and officials were unwilling to rescind their use. So the records were consulted (in those days the personalized plate database was nothing more than a small box of 3" x 5" index cards with requested combinations arranged in alphabetical order), and it turned out that no D.C. resident had ever ordered a personalized plate with HMV on it, which put the issue to rest. We also pointed out that citizens with the initials D.P.L. were already prohibited from obtaining personalized plates with their initials on them, so there certainly was a precedent for having a system that unfortunately prevented the use of certain personalized plates."

With the type designation (prefix) letters determined, attention turned to the numbers that would follow. Since the adoption of uniform 6" x 12" plates throughout the U.S. in the mid-1950s, the District had generally included a minimum of three numerals on non-passenger plates. Serial numbers below 100, with leading zeros (e.g. CA-012), were initially used, however with the adoption of black-on-white non-passenger plates in March 1965 the starting point for non-passenger series was changed to 101 (e.g. commercial plates began at C-101.) (A notable exception was made for diplomatic plates, of which the most senior ambassadors were assigned the lowest numbers beginning with DPL-1.) Members of the DCACC committee wanted the new plates to begin with number HMV 1, but the DMV refused, stating that its policy was to include at least three number on all non-passenger plates. "They did back down to a little, agreeing to start the series at HMV 001, but we held out for starting it at HMV 1" writes Mr. Lackie. "In one meeting the DMV stated that they did not want to preclude someone with the initials H.M.V. from getting personalized plates with numbers HMV 1, HMV 2, etc., and that, in fact, those numbers might already be in use on personalized plates, and officials were unwilling to rescind their use. So the records were consulted (in those days the personalized plate database was nothing more than a small box of 3" x 5" index cards with requested combinations arranged in alphabetical order), and it turned out that no D.C. resident had ever ordered a personalized plate with HMV on it, which put the issue to rest. We also pointed out that citizens with the initials D.P.L. were already prohibited from obtaining personalized plates with their initials on them, so there certainly was a precedent for having a system that unfortunately prevented the use of certain personalized plates."

After literally months of wrangling, this contentious issue finally had to be referred to the director of the D.C. DOT, Douglas Schneider. The auto enthusiasts argued that there was no logical reason why the series should not start with HMV 1, especially because the District had in its early years issued low numbers of various types. Mr. Lackie suspects that the DOT director thought the dispute was a tempest in a teapot, and that he soon became exasperated with the DMV for fighting over what appeared to be a relatively trivial matter. As a result, he agreed with the DCACC\'s position and ordered that plates of the new type be numbered beginning at HMV 1. The final color scheme, featuring the graphically printed HMV prefix, Capitol image, and city and type names in blue, the graphic D.C. flag image and embossed border and registration number in red, and a reflective white background, was settled upon. "While we were pleased with the numbering decision," recalls Mr. Lackie, "the DMV found a way to get back at us."

Assignment of the Lowest Numbers

The new HMV plates were expected to be delivered in early 1979, and the small DCACC committee that had been so involved with their creation for several years requested whether it might have some influence over to whom certain numbers were issued. Specifically, it was proposed to Mr. Schneider that he approve assignment of the 20 lowest numbers to dues-paying members of the committee. He agreed, and Rogers, Lackie and their team sat back and waited for their plates to arrive. In the meantime, Mr. Lackie drafted a press release in which provisions of the new law were outlined and a proposed letter to be sent to all owners of eligible vehicles, both documents being promptly submitted to the DMV for its consideration. Neither apparently was ever used, although a far more brief announcement was issued on March 14, 1979.

Although the two leaders of the HMV effort, Messrs. Lackie and Rogers, decided to split plates HMV 1 and HMV 2 between themselves, ultimately neither received either number. Although Mr. Schneider is thought to have directed the DMV to not issue any plates of the new type until DCACC members had a chance to obtain the first 20, by February 1979 none of the auto hobbyists had heard anything about them. Upon investigating they discovered that not only had the plates already been delivered to the DMV, but the first two had already been issued. Plate HMV 1 had been assigned to an attorney who had noticed an official legal announcement about the change in the law and had been alerted by someone in the DMV when the plates were delivered. He promptly appeared at DMV headquarters and insisted that under the law he was entitled to register his car. "Schneider offered to try to recover the plates so that they could be issued to Rogers and me," recalls Mr. Lackie, "but he was dubious about the legality of such an action. Rogers and I decided that we had pushed the system about as far as it would go, and we dropped the matter. Schneider did, however, chew out new DMV director Robert Thompson for allowing the first two plates to be released without his authority, and while it certainly didn\'t get us back the two lowest numbers, it did ensure that our committee members received very solicitous treatment by the DMV after that. In fact, we found Thompson both competent and easy to deal with. For example, our new law required that all historic vehicles had to undergo a final safety and originality inspection prior to qualifying for HMV tags. One of my vehicles was in pieces all over the garage at that time, and was completely inoperable. The DMV issued the HMV plates for it anyhow."

Although the two leaders of the HMV effort, Messrs. Lackie and Rogers, decided to split plates HMV 1 and HMV 2 between themselves, ultimately neither received either number. Although Mr. Schneider is thought to have directed the DMV to not issue any plates of the new type until DCACC members had a chance to obtain the first 20, by February 1979 none of the auto hobbyists had heard anything about them. Upon investigating they discovered that not only had the plates already been delivered to the DMV, but the first two had already been issued. Plate HMV 1 had been assigned to an attorney who had noticed an official legal announcement about the change in the law and had been alerted by someone in the DMV when the plates were delivered. He promptly appeared at DMV headquarters and insisted that under the law he was entitled to register his car. "Schneider offered to try to recover the plates so that they could be issued to Rogers and me," recalls Mr. Lackie, "but he was dubious about the legality of such an action. Rogers and I decided that we had pushed the system about as far as it would go, and we dropped the matter. Schneider did, however, chew out new DMV director Robert Thompson for allowing the first two plates to be released without his authority, and while it certainly didn\'t get us back the two lowest numbers, it did ensure that our committee members received very solicitous treatment by the DMV after that. In fact, we found Thompson both competent and easy to deal with. For example, our new law required that all historic vehicles had to undergo a final safety and originality inspection prior to qualifying for HMV tags. One of my vehicles was in pieces all over the garage at that time, and was completely inoperable. The DMV issued the HMV plates for it anyhow."

Denied either number 1 or 2, Mr. Rogers decided that he would rather have number HMV 52 to go on his 1952 Hudson, so Mr. Lackie wound up with both numbers 3 and 4. He also later obtained numbers 5 and 10 after members of the DCACC moved out of Washington or sold their cars.

Epilogue

In a March 1979 letter penned by Mr. Lackie to Mr. Schneider in which he thanked him for his intervention on the registration number issue earlier that year, Lackie also inquired if he would be willing to sell the leftover Antique Car plates to collectors. In his response, Schneider stated "we have decided to retain them for the Department\'s own archives." That long-ago decision did not remain in force, as all 25 of the remaining pairs eventually leaked out to collectors. The last D.C. Antique Car plate actually issued appears to have been number A-224. Mr. Lackie was given number A-225 by Mr. Schneider as a souvenir, and presumes that it would have been the next number issued. "I\'m only sorry I didn\'t think to register one of my historic vehicles under the new law but before the new HMV plates were available," he laments today. "Presumably the DMV would have been forced to issue me one of the old Antique Car plates for my Historic Motor Vehicle. Hindsight is always 20-20!"

Information provided on this page about two relatively obscure D.C. registration and plate types was provided almost exclusively by Skip Lackie, who organized and led the campiagn that resulted in HMV replacing Antique Car in early 1979. DCplates.com is sincerely grateful for his willingness to carefully document and share his knowledge of the process. Were it not for Mr. Lackie\'s work on this page, essentially no information about the creation of HMV plates would likely have ever been documented and preserved.

|

|

This page last updated on January 19, 2024 |

|

|

copyright 2006-2024 Eastern Seaboard Press

Information and images on this Web site may not be copied or reproduced in any manner without consent of the owner. For information, send an e-mail to admin@DCplates.net |