Pre-1918 Vehicle Registrations and License Plates

Introduction

On this page and a separate one that supports it we have addressed the oft-asked question about which registration numbers were assigned annually from 1907 through 1917. (We still don't exactly know, by the way.) On these two pages we have presented almost everything that we've been able to learn about what happened in the District of Columbia regarding motor vehicle registrations before dated annual plates were introduced as of January 1, 1918. We have tried to be as clear as possible as to what information is known with certainty, what is assumed based upon reasonably reliable evidence, and what is pure speculation due to a lack of credible evidence. The bases of estimates made are explained, and we suggest that you read and understand these estimates before relying upon conclusions drawn from them, especially with respect to registration numbers assigned annually.

Unfortunately, there is little reliable information about the registration of vehicles in D.C. during this era; less, in fact, than what may be found for many of the states. The District of Columbia required registration very early, in 1903, before all nearby jurisdictions and a full decade earlier than some of the states. States that adopted vehicle-related regulations in later years usually relied heavily on laws already on the books in other states, but the pioneer jurisdictions, including D.C., crafted their own regulations based largely on trial and error.

We hope to soon begin new research aimed at answering some of the common questions about D.C. vehicle registrations of this period. Presented on these pages today is simply an interpretation of data that has been available for many years. As new research is undertaken we hope to be able to modify the information that follows to provide greater detail and answer some nagging questions.

Putting The Plates in Context

A variety of factors contributed to the need of local and state governments at the dawn of the twentieth century to tax and regulate the use of motor vehicles and their operators. In September 1893 the nation's first practical (by standards of the day) self-propelled machine was operated on the streets of Springfield, Mass., by Charles E. and J. Frank Duryea. Four years later, no less than four companies were organized for the purpose of producing motorized vehicles. Although these early cars were crude, often little more than the chassis and body of a horse-drawn buggy with a small, simple engine installed, within a decade cars were large and fast enough that they began to take a serious toll on roads designed for slower, more gentle traffic powered by oats rather than gasoline, steam, and electric batteries. Revenue needed to be raised to fund road maintenance and construction, and the increasing number of vehicles needed to be tracked. Registration was the answer, and license plates soon followed.

In April of 1901, New York became the first state to require that vehicles be registered, but motorists were required to make or otherwise procure their own markers (first with their initials, later with assigned numbers). Like D.C., a registration law took effect in Massachusetts in 1903, although that state provided motorists with uniform plates, making them the nation's first state-issue plates. In 1904 Rhode Island became the second state to require registration and provide uniform plates, and other states, mostly in the Northeast, followed in the ensuing years. By the end of 1910 state-issue plates were provided to vehicle owners in 19 of the 46 states, and five years later motorists in 44 of the 48 states received uniform plates when registering their vehicles.

In the early twentieth century the United States and its cities, including Washington, were far different places than they are today, and the ways in which motor vehicles were used and perceived were completely different. Quite simply, from 1903 through at least the mid-1910s automobiles were not looked upon as a means of regular transportation, and horse-drawn vehicles still reigned supreme. “...in the majority of instances automobiles and motorcycles are maintained rather for purposes of recreation than to meet the requirements of the workaday world,” wrote the Washington Post in August 1909. News of the “automobilists” was first covered in the sports section of the local newspaper. Later, most papers dedicated a separate section, usually in their Sunday edition, to stories and advertisements that appealed to those engaged in what was still a pastime, a diversion. Most people that had cars used them only during the portion of the year that the weather was warm, for the first practical and affordable closed car did not debut until the early 1920s, and open cars (touring cars and roadsters) were, well, open to the elements. In the early years there were no gas stations, of course, so fuel was typically purchased at a hardware store or similar supplier. Very little of what today we associate with automobiles, such as good roads, durable tires, and safety features designed into vehicles existed during the period herein addressed. Therefore, to truly understand and make sense of vehicle registrations a century ago we need to make a conscious effort to not to correlate vehicles today, how we use and think of them and how they fit into our culture, with vehicles of 100 (and more) years ago.

Today's license plate collectors routinely classify plates by their year of issue (or sometimes their year of expiration), which presents a problem when considering pre-1918 D.C. plates. Not only are records not known as to which numbers were assigned annually, but in the historical context of these plates being issued and used this really is a moot point. Remember that vehicles themselves were a product of new technology and not part of the popular culture. Registrations were a completely new idea, and never in D.C. were they thought of as relating to a particular time period. Registrations and plates used from 1903 through late 1907 and again from late 1907 through 1917 were considered permanent. They were never associated with a calendar year, fiscal year, or other time period, and the expiration of a registration was not a consideration until 1917: it simply never happened.

Although nearby states issued annual registrations and plates during portions of D.C.'s permanent plate era (Maryland introduced annual, dated plates in 1910, Virginia in 1906, Pennsylvania in 1906, and Delaware in 1909), D.C. residents didn't have to think about annual registrations, plates, and fees, and some may not have even known about them until 1918. It is true that due to a lack of registration reciprocity among these jurisdictions motorists that traveled outside of the District had to also register their vehicles in states in which they regularly traveled, so most probably did know about annual registration procedures, but the concept was not applied within Washington until relatively late. Therefore, some could argue that the value of our desire to associate a particular calendar year with plates used in D.C. from 1903 through 1917 is negligible.

Jan. 1901-Aug. 1903: Before Registration

The issue of motor vehicle registration was first raised in the District of Columbia as a result of a letter sent to the commissioners by Major Richard Sylvester, superintendent of police, on or about January 18, 1901. According to a 1909 Washington Post article about the (then relatively short) history of motor vehicles in the city, in his letter Maj. Sylvester “recommended that automobiles, locomobiles, and kindred vehicles be inscribed on the rear of such vehicles with a number so that the same might easily be read from the sidewalks or streets.” The proposed registration fee was $2. Recommendations of the police superintendent and others were incorporated into Senate Bill no. 6822, introduced on the final day of January 1901, but it failed to pass.

Whether a similar measure was proposed in early 1902 is unknown, but it is easy to assume that one was because the number of vehicles was slowly but steadily increasing during this period, and whatever issues arose or problems were caused by autos in late 1900 to compel the police superintendent to suggest in Jan. 1901 that vehicles be regulated could only have increased during 1901 and into 1902. The District's first registration law, that of 1903, presumably was the result of an effort led by Maj. Sylvester in conjunction with his continuing efforts to maintain order on the city's thoroughfares.

It is unusual that the issue of vehicle regulation should first arise during the winter, when far fewer vehicles were in evidence as opposed to during the summer months. Indeed, in late 1900 and early 1901 it is difficult to imagine that there were 50 horseless carriages within the city. Perhaps the actual vehicle population was far less than this number. (We believe that slightly less than 400 vehicles were owned by D.C. residents when a registration law finally took effect two-and-one-half years later, in August 1903.) The commercial manufacture of motor vehicles in this country had commenced less than four years earlier.

Aug. 1903-Sept. 1907: The Prestate Era

Automobiles owned by District of Columbia residents were first required to be registered, and their operators licensed, under a city police regulation (hereinafter referred to as the “motor vehicle law” or simply “the law”) that took effect in August 1903. For each registered vehicle a number was assigned but no license plates were provided, rather it was up to each motorist to display the number on the back of his or her vehicle in accordance with the law. Usually motorists made their own plate, sometimes they assembled one from a commercially-available kit, and occasionally they painted the number directly on their vehicle. This system of vehicle identification lasted just over four years, through September 1907.

The First Motor Vehicle Law

Throughout the twentieth century (and still today), all legal and regulatory authority in Washington, including the registration of vehicles and licensing of their operators, was vested in Congress, and all funds required for operation of the city's government were Congressionally appropriated. In other words, even though Washingtonians have no voting representation in Congress, that body has always been its equivalent of a state's legislature. Both the House and Senate have committees that, through their power, facilitate day-to-day operations of city government. In 1903 these operational functions were the responsibility of a Board of Commissioners, its three members being appointed by the president and confirmed by Congress. (Since 1974 an elected mayor and city council have administered city government. Information about the operational structure of the D.C. government since 1790 is provided here.)

Although documentation to confirm this assumption has not yet been identified, we believe that it was the superintendent of police, Major Richard Sylvester, who initiated the 1903 effort that resulted in the police regulations being changed so as to require that motor vehicles be registered. Maj. Sylvester led the city's law enforcement agency from July 1898 through April 1915. That a registration bill had again been introduced in Congress early in 1903, as had occurred in Jan. 1901 (and presumably also in 1902), is evidenced by the occurrence of a hearing held by the Board of Commissioners on Tuesday, April 14, 1903, to hear the grievances of what had apparently become a fairly well-organized group of citizens opposed to the proposed regulations.

According to the Report of the Automobile Board dated Oct. 11, 1904, and included in the Report of the Commissioners of the District of Columbia for fiscal year 1904 (July 1, 1903-June 30, 1904), at the hearing the Board's president “informed those present that ‘The hearing is on the question of the adoption of a police regulation with respect to automobiles, locomobiles, and motor vehicles; and, as you are aware, this entire matter has been under discussion by the Commissioners for more than two years; that a bill has been recommended and introduced by Senator McMillan for the regulation of such vehicles. The corporation counsel had advised that legislation from Congress was not necessary, as it was within their power to meet this question under the police regulations.' The proposed regulations were read and very strong objections were offered by many of those present.”

A historical account of the hearing published by the Washington Post in 1909 provides more details: “The commissioners were anxious to have the automobilists themselves cooperate in enforcing the regulations to be acted upon. There was a good deal of agitation at that time as to whether the commissioners had the power to make and enforce rules governing the automobile traffic. At the [hearing] Commissioner MacFarland read a letter bearing on this subject from Senator McMillan. The Senator wrote: ‘Under the law permitting the commissioners to make and enforce additional police regulations for the comfort, safety, and health of the public, your board has full authority to require every person using an automobile to undergo an examination as to his or her fitness to be entrusted with a motor; to prevent such noisy locomotion as that of the recent autocarettes (at that time in operation in Sixteenth street); to prohibit such machines from making stations in front of public houses on the finest residence streets in the District; to put a stop to the fast driving by women and boys, and other ways to get control over the whole matter.'” Sen. James McMillan, of Michigan, served as chairman of the Committee on the District of Columbia in the 54th through 57th Congresses (Dec. 1895-Jan. 1903). Henry Brown Floyd MacFarland served as president of the Board of Commissioners from 1901 through 1909. “The hearing was well attended,” the Post article continues, “and many humorous objections were made to the rule requiring that all cars carry an identification number. Dr. Hasbrouck objected to having his private property numbered, stating that he did not wish to be tagged at his time of life like a convict. J.P. Lockwood declared that to number automobiles would be an outrage; that it would put a stripe on the owner, branding him as a quasi-criminal before the public.”

The 1904 Automobile Board report passage quoted above indicates that although a vehicle and driver regulation bill had been introduced in Congress in early 1903, the city attorney advised the commissioners that they could adopt and enforce vehicle regulatory rules under the police power without Congressional action. The commissioners therefore did draft vehicle-related regulations, reportedly on May 3, which were “subsequently published in the daily papers, as required by law.” At some undetermined time in late April or early May, likely after May 3 if that is indeed the date the proposed rules were drafted or finalized, the commissioners were prevented from implementing them, “it being claimed ‘that they were without authority to do so, and that the regulations themselves were unconstitutional in that they were oppressive and unreasonable and illegally interfered with private rights and property,'” according to the Automobile Board's 1904 report. A court upheld the commissioners position, “holding that ‘the Commissioners had authority to make regulations, and that the regulations themselves were wholly unobjectionable.'”

With the question of legality settled, on May 19, 1903, the city's electrical engineer, its water department superintendent, the three members of its board of examiners of steam engineers, and the vice president of the National Capital Automobile Club were appointed to comprise the newly-created Automobile Board. Nine days later the Board held its first meeting, and following the election of officers and a discussion “it was agreed that three types of [drivers] license were needed, viz, first, steam motors; second, gasoline motors; and third, electric motors; and that blanks be left on printed form that the kind of motor could be inserted therein when permits were issued. It was decided that steam motor license could cover the other two types; that gasoline motor license cover electric also, and that electric license be for that type of vehicle only.”

The fiscal year 1904 Automobile Board report actually covers a portion of fiscal 1903, as well, beginning with the Commissioner's April 14 hearing. Although it contains information about the licensing of drivers, it is mostly silent about the registration of vehicles. This is opposed to reporting in most of the states, some of which did not even require that drivers be licensed until years after vehicles were first required to be registered. In its coverage of the issuance of operator's licenses, the report indicates that the Board met 26 times during fiscal 1904, with the first meeting on Tuesday, August 11. Presumably the delay in processing vehicle-related transactions between May, when the rules were adopted, and August is due to the passing of the mandatory Congressional review period for all new laws in the District of Columbia. Congress apparently did not object to the regulations or get involved in the matter.

It was during the Board's regular meetings that applicants for licenses had to appear personally before the panel in order for their competence to be determined. All but six of the District's first 858 would-be licensed drivers were approved. It is unfortunate that similar statistics about the registration of vehicles are omitted from the 1904 report, although we do know that the first vehicle registrations were assigned at the same 26 Board meetings. In its fiscal year 1907 report to the commissioners, the Automobile Board notes that “the date of the first registration and examination [was] August 11, 1903.” A 1909 Washington Post article indicates that “in August, 1903, Frank Goodwin, of 250[fourth digit illegible] Fourteenth Street northwest, put up $1 and procured the first license” [i.e. registration]. In a 1965 Washington Post article, Harold C. Smith, 83, recalled the early days of motoring in the District, including being one of the first to whom a drivers license was issued in August 1903. “When Smith received the District license [to operate] his 1902 Reading Steamer, he was questioned by three men. 'I'm almost positive none of them had ever driven an automobile,' he said.”

Sat., August 29 (or perhaps the previous day) was apparently a deadline by which existing vehicles had to be registered and individuals operating them had to be licensed, for in its edition of that day the Washington Evening Star indicated its hopefulness that the motor vehicle law taking effect would alleviate unpleasant encounters between autoists and pedestrians in Washington:

“The amalgamated association of automobile dodgers, which includes in its membership almost every person in the District who does not own or have an interest in a motor-propelled vehicle, excepting street cars and locomotives, breathed with freedom today, it is presumed, for the first time since the smooth asphalted streets of the nation's capital became the stamping grounds for the “devil” wagon. After many months of patient waiting on the part of pedestrians, the powers that rule in this jurisdiction have proclaimed official war on the scorchers and have promulgated regulations which become effective today, and which requires the automobilist to have a license and some visible means of identification.”

An unusual characteristic of the 1903 law is that it makes no provision for a vehicle registration fee. In the states the registration fee was (and still is) essentially a user tax to fund capital projects that together comprise a jurisdiction's road transportation infrastructure. Why no fee was provided for by the commissioners is unknown, but members of the Automobile Board lobbied (unsuccessfully, it turns out) for a registration fee in almost every one of its annual reports, beginning with the 1904 edition. For example, in the 1906 report, the Board indicates that “The automobile board must urgently renew the recommendation of the last annual report that a fee of $1 be paid for registration and assignment of an identification number for a vehicle owned in the District of Columbia.” “The District of Columbia is without exception, so far as the automobile board is aware, [the only jurisdiction] that does not require a fee for either registration of the motor vehicle, or license to operate motor vehicles, or both.”

Annual Vehicle Registration-Related Activity

Reporting by the Automobile Board as to how many registration transactions were processed annually, when done at all, was done on a fiscal year, not calendar year basis. Having made certain assumptions regarding fiscal 1904 and 1908 data, which are discussed in the text that follows, below is a table in which is summarized results of our analysis of fiscal year 1904 through fiscal year 1908 annual reports of the Automobile Board. There were not multiple registration types during this period, and because plates were provided by the vehicle owner there are not separate plate types for automobiles and motorcycles. Therefore, for purposes of this table both vehicle types are combined.

Registration Numbers Assigned From Mid-Aug. 1903-Sept. 1907 |

||||||

FISCAL YEARS |

CALENDAR YEARS |

|||||

Numbers Assigned |

Numbers Assigned |

|||||

Qty. |

Sequence |

Qty. |

Sequence |

|||

1903 |

n/a |

n/a |

493 |

1-493 |

||

1904 |

783 |

1-783 |

469 |

494-962 |

||

1905 |

468 |

784-1251 |

515 |

963-1477 |

||

1906 |

506 |

1252-1757 |

542 |

1478-2019 |

||

1907 |

581 |

1758-2338 |

444 |

2020-2463 |

||

1908* |

125 |

2339-2463 |

n/a |

n/a |

||

* Registrations of the type discussed in this section were issued only for the first quarter of fiscal year 1908. |

||||||

Fiscal Year 1904 (July 1903-June 1904) and Earlier

Because it is the Board's first report, the fiscal year 1904 edition covers the period of April 11, 1903 (in fiscal 1903) through the end of fiscal 1904. Although this report is silent as to the number of registration transactions processed, information in the fiscal 1906 report (discussed below) allows us to conclude that 783 vehicles were registered during this reporting period. We have no information as to how many fiscal 1904 numbers were assigned for use on motorcycles.

In order to segregate fiscal 1904 activity by calendar year, we have estimated Oct. 1903-June 1904 monthly registrations at 75% of the number assigned during those months in fiscal year 1905 (per published data). As for the remaining 390 registrations, they have been divided between August (275) and Sept. (95) using (what we feel is) an educated guess. The August number would be unusually high because all vehicles then owned by D.C. residents had to be registered during that month.

Fiscal Year 1905 (July 1904-June 1905)

The Automobile Board's report for fiscal 1905, dated Oct. 11, 1905, is the first to include information about the registration of vehicles. It begins “There were 24 meetings held during the year (the first and third Fridays of the months), 667 applicants were examined, recommended, and given permits to operate motor vehicles; 468 motor vehicles were assigned identification numbers, 168 motor vehicles to which identification numbers had been assigned were transferred to purchasers of them, and 68 motor vehicles from different States were registered during the year.” No estimates were required in summarizing published fiscal 1905 data for the tables at the top of this sub-section. We have no information as to how many fiscal 1905 numbers were assigned for use on motorcycles.

One of the more interesting aspects of the registration system employed during this era relates to vehicles brought into the District of Columbia temporarily. Under an order of March 1, 1905, vehicle owners that established a residence in Washington for a period of not longer than 60 days could avoid having to obtain a D.C. registration by registering as a non-resident. As long as the vehicle was registered in some “State, Territory, or Federal district,” the registration number assigned by the vehicle owner's home jurisdiction, as well as their temporary address in D.C., could be registered with the Automobile Board, a process sufficient to allow the vehicle to legally be operated within D.C. Therefore, the 68 “vehicles from different States” noted above are not included in the total of 468 D.C. registrations because although they were registered with the Automobile Board, it was with a number not assigned by the Board.

Fiscal 1905 non-resident transactions were recorded throughout the fiscal year even though the order allowing this practice is referenced as “the Order of March 1, 1905.” The 86 fiscal 1905 non-resident transactions involved 26 vehicles from New York, 13 from Massachusetts, 10 from Pennsylvania, nine from Maryland, seven from New Jersey, two from Ohio, and one from Connecticut.

In their 1905 report (and again in 1906) members of the Automobile Board recommended that a small, metal marker stamped with the registration number assigned for use on a each registered vehicle be provided to the owner for display on the vehicle, a practice employed in several of the states before uniform, state-provided plates began to be issued. The topic is addressed in 1905 in conjunction with the Board's lamentations about the difficulty encountered in keeping track of registration number transfers.

From Oct. 1907 through Dec. 1917, when porcelain enamel markers were provided to motorists, a plate became obsolete when the vehicle to which it was initially assigned was sold, registered in one of the states, or taken out of service. However, before Oct. 1907 registration numbers (and perhaps usually the owner-provided markers with which they were displayed) stayed with a vehicle sold to another D.C. resident. This practice quickly became unwieldy for Automobile Board clerks, which is presumably why it was discontinued after Oct. 1907. Members of the Board addressed this in their 1905 report (despite it being so early in the history of vehicle registration and the number of vehicles and transactions affected being so relatively small), and quickly segued into a proposal to issue numbered dashboard discs (as they are called by license plate collectors today):

“Great difficulty is encountered in keeping an accurate list of owners, caused by the transferring of assigned numbers, and to prevent such transfers from the motor vehicle to which a number has been assigned to an entirely different type of vehicle, perhaps, it is recommended that on the assignment of such number the secretary of the automobile board shall issue and deliver to the owner of such motor vehicle a seal of aluminum or other suitable metal, which shall be circular in form, approximately 2 inches in diameter, and have stamped thereon the words “registered motor vehicle, District of Columbia,” with the registration number inserted therein; which shall thereafter at all times be conspicuously displayed on the motor vehicle to which such number has been assigned. Upon the sale of said motor vehicle, the vendor shall report immediately such sale, and return the registration seal affixed to such motor vehicle. It is further recommended that all motor vehicles owned and operated in the District of Columbia be required to procure and display such [a] registration seal.”

Despite this proposal, and an identical one made in the Board's fiscal 1906 annual report, the discs described are thought to have never been approved and issued. The absence of a similar proposal in the 1907 report is reasonable only when considering that by the time of its publication, uniform, Board-provided plates were already being issued.

Fiscal Year 1906 (July 1905-June 1906)

The Automobile Board's report for fiscal 1906, dated Oct. 10, 1906, is the first to include data about the registration of motorcycles. The report begins “There were 24 meetings held during the year (the first and third Fridays of the months), 879 applicants were examined, 873 recommended and given permits to operate motor vehicles, 6 rejected as not competent; 506 motor vehicles were assigned identification numbers, 246 motor vehicles to which identification numbers had been assigned were transferred to the purchasers of them, and 89 motor vehicles from different States were registered during the year.” These 89 foreign vehicles were based in 13 states and Canada.

Forty-three of the 506 registered vehicles were motorcycles. Of the 463 remaining, 297 were powered by gasoline, 114 by electric batteries, and 52 by steam. No estimates were required in summarizing published fiscal 1906 data for the tables at the top of this sub-section. The number of vehicles likely to have been registered during fiscal year 1904 is determinable because the numbers registered during 1905 and 1906 are well-documented, and the fiscal 1906 annual report includes this statement: “There were registered 1,757 motor vehicles of all kinds at the close of the fiscal year, and permits had been issued to 2,377 operators from the date of the first examination, held August 11, 1903.” We believe that the quantity 1,757 represents the number of registrations that had been assigned through June 30, 1906, not necessarily the number in use at that date, despite the manner in which this number was reported by the Board.

Fiscal Year 1907 (July 1906-June 1907)

The Automobile Board's report for fiscal 1907, dated Nov. 6, 1907, begins “There were 24 meetings held during the year (the first and third Fridays in each month), 1,031 applicants were examined, 990 recommended and given permits to operate motor vehicles, 41 rejected as not competent; 546 motor vehicles were assigned identification numbers, 352 motor vehicles to which identification numbers had been assigned were transferred to purchasers of them, [and] 127 motor vehicles from different States were registered during the year.”

One adjustment, to add 35 vehicles to the quantity of registration numbers assigned during the year as indicated in the section of the report in which current-year activity is presented, has presently been made. The Board indicated in its fiscal 1906 report that 1,757 numbers had been assigned through the end of that year (i.e. June 30, 1906), and current-year information in the fiscal 1907 report indicates that 546 numbers were assigned, which would bring the cumulative total at June 30, 1907, to 2,303. However, the Board indicates in its 1907 report that “2,338 vehicles of all kinds” had been registered by the end of the year. This reported cumulative total has been relied upon, thus the variance, 35 vehicles, were added to the 546 fiscal 1907 total. For purposes of estimating the quantity of numbers assigned during calendar years 1906 and 1907, the 35 extra vehicles were added to months in proportion to the timing of the registration of the 546 vehicles reported.

By late fiscal 1907 (i.e. during the first half of calendar year 1907) it was already known that owner-provided plates would soon be replaced by uniform plates provided by the Automobile Board. Purchase of the first batch of plates is addressed by the Board as follows: “The act making appropriations to provide for the expenses of the government of the District of Columbia for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1908, and for other purposes provides ‘for the purchase of enamel metal identification tags for motor vehicles in the District of Columbia three hundred dollars, or so much thereof as may be necessary; and the Commissioners of the District of Columbia are hereby authorized to amend the regulations controlling motor vehicles so as to provide for such identification tag and registration thereof; the owner of each motor vehicle shall pay the sum of one dollar [for the tag], and the secretary of the automobile board shall, after the payment of said fee to the collector of taxes, District of Columbia, issue to said owner the identification number tag.'”

Also in its 1907 report did the Automobile Board suggest that the Commissioners address the issue of motorists displaying license plates from more than one jurisdiction on their vehicles. At first consideration, the discussion (copied below) appears to address the issue of registration reciprocity, which later was a contentious one, especially between D.C. and Maryland. However, a second reading suggests that the issue may be simply one of the confusion that likely arose when more than a single plate was displayed on a vehicle, which could have occurred since Maryland's first registration law took effect in the spring of 1904. In other words, it appears that the Board is not necessarily addressing in which jurisdictions motorists must register their vehicles, but rather just whether they should be allowed to simultaneously display more than a single plate on their vehicles and, if so, which jurisdiction's plates would be allowed.

The Board's statement on this issue follows: “The identification numbers carried on motor vehicles should in the opinion of the board be restricted to those of the District of Columbia and the State of Maryland and the State of Virginia on all vehicles owned and registered in the District of Columbia. The State of Maryland is especially named because of [a revision to] the Maryland motor-vehicle law which, by the act of the legislature, approved April 8, 1906, contains the following: ‘No number other than Maryland State number shall be carried upon the front and back of the said motor vehicle while operated or used on any of the public highways of this State aforesaid; provided that residents of the District of Columbia shall not be required to remove the District number or tag when coming into Maryland if such tag contains the initials ‘D.C.' in plain letters not less than one-half inch in height after such District license number.'”

Fiscal Year 1908 (July 1-Sept. 30, 1907 only)

The period of fiscal year 1908 during which motorists were required to provide their own license plate is relatively short, and how and exactly when the transition from owner-provided plates to uniform, Automobile Board-provided porcelain plates in early October occurred is unknown. Not surprisingly, the Board's fiscal 1908 annual report, issued almost 14 months after the transition, is silent on the matter. It must be borne in mind that the transition from owner-provided to uniform plates was simply that: a plate change. There was no new registration law, no registration fee or annual renewal requirement was implemented, and no other noteworthy changes to the registration process occurred. Essentially all that happened is that homemade plates then presently in use were replaced with Board-provided porcelain ones, and presumably at this time the Board was able to cull from its records vehicles that were no longer in use in the District because their owners would not have called for their new plates. Otherwise, however, despite how license plate collectors and this resource consistently make a distinction between the prestate and porcelain eras because the plates are so different, there was in fact very little difference between the two periods.

The Automobile Board's fiscal 1917 annual report includes a statement to the effect that D.C.'s undated, white-on-black porcelain license plates were first issued on October 8, 1907, a Tuesday. During the period of Tue., Oct. 1-Mon., Oct. 7, which includes five weekdays, we do not know whether any new registrations were issued; and, if any were, whether porcelain plates were distributed. The Board's fiscal 1908 report indicates that 973 non-motorcycle and 23 motorcycle registrations were issued during October 1907, but we do not know whether any of these transactions occurred before the new porcelain plates were ready for distribution, which presumably would have been handled in a manner prescribed by the regulations discussed and quoted above. Regardless, D.C.'s prestate era appears to have come to an end sometime between Sept. 30 and Oct. 7, 1903.

Prestate License Plates and Registrations

As occurred in many states, the earliest, owner-provided license plates used in the District of Columbia took many forms, most often leather pads with metal house numbers attached. The only requirements as to the manner in which registration number was to be displayed is that the figures had to be at least 3” high with a stroke (the width of lines comprising the numbers) of at least 3/8”.

The 1903 motor vehicle law required only the display of the registration number, not any indication that the vehicle was based in the District of Columbia. Because prestate plates began to be used in Maryland in May 1904 in conjunction with that state's first registration requirement, included in the Automobile Board's 1904 annual report is this statement: "On account of the similarity of numbers carried, especially on motor vehicles owned in the District of Columbia and also registered in Maryland, it is recommended that all motor vehicles, 'the motive power for which is electricity, steam, gas, gasoline, oil, naphtha, or other similar source of energy,' required by the police regulations to carry a number for identification purposes have added the letters 'D.C.' to the assigned number (thus 1000 D [over] C), this being required in several of the States from whose laws extracts have been quoted. This is the only way that the police will be able to identify those who violate the regulations." Fifteen days after the Oct. 11, 1904, date of the Board's 1904 report, a regulation took effect "requiring the initial letters 'D.C.' to be added to the identification number on motor vehicles owned and operated in the District of Columbia. (Order Oct. 29, 1904.)" The change is reflected in this version of Article XXIV, Section 2 of what is presumably the Police Regulations of the District of Columbia, which provided vehicle owners with guidance in their preparation of a single license plate for each of their vehicles:

“Each machine shall be identified by a number, which shall be conspicuously displayed upon the rear of the vehicle, so as to be plainly visible, the figures to be separate Arabic numerals not less than three inches high, and the strokes not less than three-eights of an inch in width; and also as a part of such number the initial letters D.C. (placed perpendicularly after the numerals) each letter to be not less than one inch in height. Numbers shall not be transferred from one vehicle to another, nor shall machine numbers be loaned from one person to another, nor shall fictitious numbers be used.”

Contrary to information published previously to the effect that the lowest assigned D.C. registration number during this period was 100, in fact numbers are known to have been assigned sequentially beginning at 1. The Automobile Register and Road Book for Maryland, District of Columbia, and Adjacent Territory published in 1906 by the Automobile Register Co., of Baltimore, lists 862 D.C. registrations with the lowest and highest numbers being 2 and 2136, respectively. Note that only 40% of the first 2,136 registrations were still valid by whatever point in (presumably) 1906 the data was compiled for publication. Of the 862 registrations, 771 (89%) were assigned to individuals and entities that listed a D.C. address as their address of record. The remaining 91 (11%) listed addresses in the states, most in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast but including one from Alabama and another from Chicago. With only a few exceptions all of the registrations listed in the 1906 book appear to have been assigned to individuals. There appears to have been a distinct interest in the lowest numbers, 1-99, for 63 of them were still in use whereas from number 100 through 999 the average number of listed registrations in each 100-number block (100-199, 200-299, etc.) is 48.

Contrary to information published previously to the effect that the lowest assigned D.C. registration number during this period was 100, in fact numbers are known to have been assigned sequentially beginning at 1. The Automobile Register and Road Book for Maryland, District of Columbia, and Adjacent Territory published in 1906 by the Automobile Register Co., of Baltimore, lists 862 D.C. registrations with the lowest and highest numbers being 2 and 2136, respectively. Note that only 40% of the first 2,136 registrations were still valid by whatever point in (presumably) 1906 the data was compiled for publication. Of the 862 registrations, 771 (89%) were assigned to individuals and entities that listed a D.C. address as their address of record. The remaining 91 (11%) listed addresses in the states, most in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast but including one from Alabama and another from Chicago. With only a few exceptions all of the registrations listed in the 1906 book appear to have been assigned to individuals. There appears to have been a distinct interest in the lowest numbers, 1-99, for 63 of them were still in use whereas from number 100 through 999 the average number of listed registrations in each 100-number block (100-199, 200-299, etc.) is 48.

Oct. 1907-Dec. 1917: The Porcelain Era

The District government required that all vehicles in use in the fall of 1907 be re-registered, evidence of compliance being shown with an undated white-on-black porcelain enamel plate provided to each motorist by the Automobile Board for a $1 plate fee. There was no registration fee throughout this era.

D.C. 1907-17 porcelain plates could legally be displayed only on the vehicle to which they were first assigned, which is to say they could not be transferred to another vehicle or individual (as could registration numbers and the underlying registrations assigned during the prestate era). When a vehicle was sold its new owner had to purchase a new plate, and the individual selling the vehicle could not transfer the registration and plate to a different vehicle.

Although relatively minor design changes were made during the 10-year life of this issue, there was indeed only a single issue of plates during this period. While most states in which vehicles were registered were issuing dated plates annually, D.C. stuck to this one undated plate, perhaps because there still was no annual registration renewal transaction or fee. This era ended when a series of annual, dated, embossed steel plates began to be issued for 1918, at which time registration fees began to be charged.

Introduction to the Registration of Vehicles

To understand the pre-1918 era of D.C. license plates we must not compare its plates, and the system under which they were issued, to plates and registration systems of today. Throughout D.C.'s porcelain era, from October 1907 through the end of 1917, vehicle registrations were permanent and free, and there was only a single type. Because this is so unusual by today's standards, these basic facts bear repeating: From 1907 through 1917 in the District of Columbia there was never a registration fee and there was only a single vehicle classification for registration purposes. Special registrations were not issued for trucks, commercial vehicles, motorcycles, trailers, or dealer- and manufacturer-owned vehicles.

Upon purchasing a vehicle, new or used, the owner had to register it with the city government's Automobile Board (which also licensed drivers) and simultaneously buy a single license plate, the cost of which was initially $1. The plate fee was increased to $2 in April 1908, where it remained through 1917.

Because from 1907-17 there was only a single class of vehicle, there was only one sequence of registration numbers. D.C. plate numbers of this era were assigned beginning at 1 in 1907 and were assigned sequentially, to numbers above 64000, before the permanent plates all were replaced at the end of 1917. There were, however, two styles of license plates because it was determined, shortly after the porcelain plates began to be distributed in 1907, that their size made them unsuitable for use on motorcycles. Therefore, specially-designed plates were procured and subsequently sold to motorcycle owners, but only the plates themselves, not the corresponding registrations, differed from those provided to owners of all other types of motor vehicles. Throughout this section, license plates of the two styles are referred to as "full-size" and "motorcycle."

Because all registrations were of the same type, numbers on motorcycle plates were drawn from the single sequence of numbers used for all motor vehicle registrations. First, numbers 2501-3100 were made on the first style of motorcycle plate, which we believe was essentially a miniature version of the regular plate. (No examples are known today). Therefore, after full-size plate 2500 was assigned, 3101 was distributed next. As the supply of motorcycle plates in the 2501-3100 sequence dwindled, officials had a new series, now white on red and in a vertical format, made with numbers 5000-5999. Other blocks of numbers were made on undated, white-on-red, vertical-format motorcycle plates throughout the porcelain era, leaving gaps in the sequence of numbers made on full-size plates.

The curtain closed on the District's homemade plate era at the end of October 1907. A September 15, 1907, article in the Washington Star-News in which the availability of the first government-issued plates was announced indicated that the new plates were being issued because there was too little uniformity in plates displayed during the past several years, and that some operators “pick[ed] numbers to suit themselves.” Replacing the variety of owner-provided markers were uniform, white-on-black undated porcelain-enamel plates, issued singly, that were provided by the D.C. government and used for ten years. They were first issued on Oct. 8, 1907, and all holders of existing registrations received one during October. There are two distinct versions of this plate, the difference being evident in the height of letters in which DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA is displayed across the top, with more subtle differences existing in both styles.

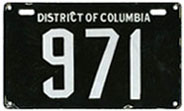

The first 2,500 D.C. porcelain plates are numbered 1 through 2500 and are characterized by a relatively light gauge of iron and thin layer of enamel as opposed to later plates. They are 6” high and 10” wide, have DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA printed in letters one-half inch high, and are described in the aforementioned Star-News article as a “very credible and practical sign.” An October 23, 1907, Washington Post article corroborates that "The District has procured 2,500 of the new tags."

On the back of each plate is an advertisement for the Washington company of Lamb & Tilden, located at 723 13th St., NW. The message promotes brass automobile name plates, a popular accessory of the day made by many companies, apparently including Lamb & Tilden. Because the only way that auto manufacturers identified their products at the time was a small badge affixed to the radiator tank, it was a popular custom for motorists to display the maker's name with a large, brass nameplate affixed diagonally to the radiator, usually in a script font (so that a name could be displayed with a single piece, not individual letters). These nameplates were stencil-cut so as to not obstruct air flow to the radiator.

On the back of each plate is an advertisement for the Washington company of Lamb & Tilden, located at 723 13th St., NW. The message promotes brass automobile name plates, a popular accessory of the day made by many companies, apparently including Lamb & Tilden. Because the only way that auto manufacturers identified their products at the time was a small badge affixed to the radiator tank, it was a popular custom for motorists to display the maker's name with a large, brass nameplate affixed diagonally to the radiator, usually in a script font (so that a name could be displayed with a single piece, not individual letters). These nameplates were stencil-cut so as to not obstruct air flow to the radiator.

Lamb & Tilden's message also promotes its role as a supplier of “stamps and attachments for license plates; rubber and metal stamps;” and “seals, stencils, etc.” In the days before bumper stickers, embossed metal plates with names of municipalities and political candidates, for example, were commonly attached above or below a vehicle's license plate, or otherwise mounted to vehicles, and badges and club insignias were also often similarly displayed. Lamb & Tilden was apparently in the business of supplying these types of items to the motoring public. Whether they actually produced or just supplied the first Washington, D.C. license plates is unknown for certain, but we believe the latter to be the case. The manufacture of porcelain plates and signs was a labor- and capital-intensive process, so based upon the company not being known to have ever produced any other vehicle registration plates and because porcelain goods of any kind are not mentioned in the advertisement, it is assumed that they were not a porcelain plate manufacturer. It seems more likely, then, that being in the business of identification products in Washington, that they acted as a manufacturer's agent to supply plates to the D.C. government.

Despite past reports that registration numbers of this era were assigned beginning at 100, there appears to be no question that they were in fact issued starting at 1.

- Photographs are known of D.C. porcelain plates numbered 11, 24, and 26 in use.

- In their appeal to the Board of Commissioners for an annual registration and license plate system, members of the Automobile Board wrote in their 1915-16 Annual Report “One of the most needed pieces of legislation at the present time is a law providing for the annual licensing of automobiles. At the present time they are numbered serially, starting with No. 1, issued on October 8, 1907.”

- A 1912 D.C. registration listing book, The Automobile Register of the District of Columbia (fourth edition, copyright 1912), provides data for registration numbers then in use, with 1 being the lowest (and 11060 the highest).

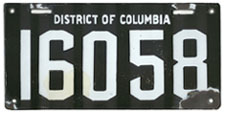

The next two batches of D.C. porcelain plates, those numbered 3101 through 4999 and 6000 through 9999 (because registration numbers 2501 through 3100 and 5000 through 5999 were set aside for assignment to motorcycle owners, as discussed below), retain all visible characteristics of the Lamb & Tilden plates but were made by the Baltimore Enamel & Novelty Co., of Baltimore, Maryland. This company, which made porcelain plates for a number of the states, imprinted its logo on the back of each plate. Unlike the earlier plates, these and later plates have grommets affixed to the small hole in each corner.

Plates 10000 through about 19900 are identical to plates from the previous batch, including Baltimore Enamel and Novelty's seal on the back, except that the length was increased from 10” to 12” to accommodate the fifth digit in the number. Interestingly, these plates are the same dimensions, 6”x12”, as modern North American plates.

Plates 10000 through about 19900 are identical to plates from the previous batch, including Baltimore Enamel and Novelty's seal on the back, except that the length was increased from 10” to 12” to accommodate the fifth digit in the number. Interestingly, these plates are the same dimensions, 6”x12”, as modern North American plates.

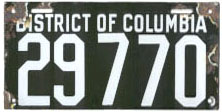

At some point between plates 19840 and 19968 the height of letters used to display DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA was doubled to one inch. Number 19840 is the highest known plate to have the small letters and 19968 the lowest with larger letters. It is reasonable to assume that the change was made with plate 19900 or 19901, but the exact change point is uncertain.

D.C. porcelain plates continued to be made by Baltimore Enamel & Novelty until the high 20000 series, when we find a small batch made by the other prominent porcelain plate manufacturer of this era, Ingram-Richardson Co., of Beaver Falls, Pa. The highest observed plate made by Baltimore Enamel & Novelty is 27417 and the lowest made by Ingram-Richardson is 29235, so the change was made at some point between these numbers. The switch back to plates made (presumably, as discussed in the following paragraph) by Baltimore Enamel & Novelty occurred at some point between numbers 30876, the highest-number plate know to have been made by Ingram-Richardson, and 35340, the lowest thought to have been produced by Baltimore Enamel & Novelty. Therefore, we know that Ingram-Richardson made at least 1,641 plates and no more than 7,923. Perhaps it made a batch of 5,000 plates, maybe from 28000 through 33000 or 29000 through 34000.

D.C. porcelain plates continued to be made by Baltimore Enamel & Novelty until the high 20000 series, when we find a small batch made by the other prominent porcelain plate manufacturer of this era, Ingram-Richardson Co., of Beaver Falls, Pa. The highest observed plate made by Baltimore Enamel & Novelty is 27417 and the lowest made by Ingram-Richardson is 29235, so the change was made at some point between these numbers. The switch back to plates made (presumably, as discussed in the following paragraph) by Baltimore Enamel & Novelty occurred at some point between numbers 30876, the highest-number plate know to have been made by Ingram-Richardson, and 35340, the lowest thought to have been produced by Baltimore Enamel & Novelty. Therefore, we know that Ingram-Richardson made at least 1,641 plates and no more than 7,923. Perhaps it made a batch of 5,000 plates, maybe from 28000 through 33000 or 29000 through 34000.

Plates with numbers higher than those marked as having been made by Ingram-Richardson are not marked as to their maker, although they have one distinguishing characteristic (other than the number) to set them apart from the Ingram-Richardson and earlier plates: the back is covered in black porcelain enamel, not white as on all previous D.C. porcelain plates. This common characteristic leads us to conclude that they all were made by a single manufacturer. Newspaper accounts of 1916, by which time the black-back plates were being issued, indicate that D.C. plates were being ordered from “a Baltimore firm” but do not specify the manufacturer. It is reasonable to assume that this company is Baltimore Enamel & Novelty due to its prominence in this business and its having previously made D.C. plates, although other Baltimore companies were then engaged in the manufacture of porcelain wares, including license plates.

Plates with numbers higher than those marked as having been made by Ingram-Richardson are not marked as to their maker, although they have one distinguishing characteristic (other than the number) to set them apart from the Ingram-Richardson and earlier plates: the back is covered in black porcelain enamel, not white as on all previous D.C. porcelain plates. This common characteristic leads us to conclude that they all were made by a single manufacturer. Newspaper accounts of 1916, by which time the black-back plates were being issued, indicate that D.C. plates were being ordered from “a Baltimore firm” but do not specify the manufacturer. It is reasonable to assume that this company is Baltimore Enamel & Novelty due to its prominence in this business and its having previously made D.C. plates, although other Baltimore companies were then engaged in the manufacture of porcelain wares, including license plates.

The highest number made and highest number issued are both unknown. The highest documented plate number is 65038 which it is reasonable to assume was issued near the end of 1917.

Click here to see images of District of Columbia porcelain license plates in use.

Records of the Automobile Board indicate that there were only two types of plates issued during the porcelain era: full-size and motorcycle. Vehicle dealers and owners of commercial vehicles and taxis received plates from the same series used for privately-owned cars.

Annual reports prepared by the Automobile Board indicate that motorcycle registrations were issued right from the start of the porcelain era, in October 1907. However, based upon news reports and an analysis of data published in the Automobile Board's Report to the Commissioners for the year ended June 30, 1908, we know that license plates were not provided to motorcycle owners until April 1908. From Oct. 1907 through March 1908 cyclists were likely compelled to provide their own plate or paint their assigned number directly on their machine.

A 1912 D.C. registration listing book, The Automobile Register of the District of Columbia (fourth edition, copyright 1912), indicates that registration numbers 2501 through 3100 had been set aside and “Issued to motorcycle owners only.” We believe that this confirms that the first batch of D.C. porcelain auto plates was numbered through 2500, and that while those numbers were being assigned for use on passenger cars beginning in October 1907, motorcycles being registered were being assigned numbers starting at 2501, although presumably without a license plate.

It appears that special license plates began to be provided to motorcycle owners on or about April 1, 1908, because that is when the $2 plate fee began to be collected from these individuals. That specially designed plates were available to cyclists by the end of the month is corroborated by a brief Washington Post article quoted here. Presumably the registration numbers were from the 2501-3100 block discussed in the previous paragraph. We know that the plates then introduced were smaller than 6" x 10", and in its 1908-1909 Report to the Commissioners, the Automobile Board reports having purchased during that fiscal year “1,278 tags 6 by 10 inches for motor vehicles and 222 tags 4 by 7 inches for motor cycles.” None of these miniature D.C. porcelain-enamel plates are known to exist today.

The 5000 series of registration numbers (5000-5999) is also missing from the aforementioned 1912 listing book but the reason for its omission is not indicated. No 5000-series 6”x12” D.C. porcelain plates are known to exist today. However, a single white-on-red, vertical-format porcelain plate with number 5627 and the letters “DC” at the bottom suggests that the 5000 series had in fact been set aside for and was used for motorcycle plates. Plate no. 5627 is curved from top to bottom so as to be more easily displayed on the rear fender of a motorcycle, and this style of cycle plate was used in other jurisdictions, including Maryland, during this era.

The 5000 series of registration numbers (5000-5999) is also missing from the aforementioned 1912 listing book but the reason for its omission is not indicated. No 5000-series 6”x12” D.C. porcelain plates are known to exist today. However, a single white-on-red, vertical-format porcelain plate with number 5627 and the letters “DC” at the bottom suggests that the 5000 series had in fact been set aside for and was used for motorcycle plates. Plate no. 5627 is curved from top to bottom so as to be more easily displayed on the rear fender of a motorcycle, and this style of cycle plate was used in other jurisdictions, including Maryland, during this era.

Four higher-numbered white-on-red porcelain motorcycle plates marked “DC” are also known, numbers 12612, 12725, 13609, and 16657. Therefore, it appears that other blocks of numbers were set aside for use with motorcycle registrations. These fender-style plates are curved not only from top to bottom, but also from side to side. That D.C. motorcycle plates of this era were made in a vertical format is confirmed by this passage from the Board's annual report for fiscal year 1916: “It is also recommended that [any regulation regarding an] annual license be made to apply to motorcycles as well as to automobiles and that motorcycle numbers should be arranged horizontally instead of vertically, as is at present the plan, and that both automobile and motorcycle number tags be flooded with light at night and that the figures be shown as through a transparency. ”

As we collect additional data about existing full-size D.C. porcelain plates and analyze later annual reports of the Automobile Board we expect to be able to refine and improve our information about pre-1918 Washington, D.C. motorcycle license plates. Further information about 1907-1917 motorcycle plates, their numbering and issuance, is provided on the page referenced below.

According to the Automobile Board's annual reports for fiscal years 1910 through 1918, during this portion of the porcelain era duplicate plates, which is to say plates with a number already in use and displayed on a porcelain plate, were specially made and provided to motorists that reported their plate having been lost or damaged to the extent that it was illegible. Although the Board makes no mention of duplicate plates having been made prior to fiscal year 1910, it is likely that they were.

Unfortunately, for only one year (fiscal 1914) is the number of duplicate plates segregated between motorcycle and full-size. In this year, 10.25% of replacements ordered were cycle plates, the remainder were full-size. If we extrapolate this result over the population of 1,523 duplicates reported to have been procured during years for which the split is not known, it appears that approximately 1,540 of the 1,718 duplicates made were full-size plates and the remainder were motorcycle plates.

Duplicate plates are not considered in our estimate of numbers assigned from 1907 through 1917 because their being provided to motorists did not result in a new registration transaction. This is how the Automobile Board reported duplicates for fiscal years 1910 through the first half of fiscal 1918:

Fiscal Year |

Reporting About Duplicate Plates |

1909 and earlier |

[no mention] |

1910 |

"There have been 103 duplicate tags procured, at actual cost to owners, from the contractor during the year." |

1911 |

"There were 110 duplicate tags procured from the contractor at actual cost to the owners." |

1912 |

"One hundred and forty-six duplicate tags were procured from the contractor for owners of motor vehicles whose tags had been lost or destroyed." |

1913 |

"Duplicate tags were procured for 178 vehicles to replace those lost and defaced." |

1914 |

"Duplicate tags were procured for 175 automobiles and 20 motor cycles to replace those lost or defaced." |

1915 |

"Duplicate tags were procured for 254 owners, the original tags being lost or so mutilated that the numbers were not able to be made out." |

1916 |

"Receipts from duplicate tags [qty. of 413]: $413" |

1917 |

"Receipts from duplicate tags [qty. of 316]: $316" |

1918 (July-Dec. 1917 only) |

"Duplicate tags for motor vehicles, at $1: [qty. of 3, receipts] $3" |

Estimate of Registration Numbers Assigned Annually

Exactly which registration numbers were issued annually during this period is unknown. As discussed above, not knowing which numbers appeared on motorcycle plates prevents us from knowing during which calendar year full-size plates with particular numbers were issued. However, our estimates of numbers assigned annually are posted on a separate page. Click here to get there.

|

This page last updated on December 31, 2017 |

|

|

copyright 2006-2018 Eastern Seaboard Press Information and images on this Web site may not be copied or reproduced in any manner without consent of the owner. For information, send an e-mail to admin@DCplates.net |